| |

The

Roxboroughs:

One Of

Detroit's

Leading

Families

By Ken

Coleman/Special

to Tell

Us USA

DETROIT

- The

Roxboroughs,

five

generations

of

lawyers

along

with

artists,

entertainers,

and

socialites,

dominated

newspaper

headlines

and

gossip

columns

during

the

1930s

and

1940s.

Their

professional

achievement,

at times

historic,

and

their

personal

exploits,

at times

embarrassing,

made

them

household

names.

RACE

MAN IN

NOLA

Charles

A.

Roxborough

II, an

African

American,

moved

his

family

to

Detroit

in 1899

from New

Orleans,

Louisiana

where he

had been

active

in

Republican

Party

politics.

In fact,

he fled

New

Orleans

during a

period

of white

backlash

exhibited

by

regressive

and

racist

Jim Crow

laws and

codes

against

political

and

economic

gains

earned

by

blacks

after

the

Civil

War. He

bolted

from the

Republican

Executive

Committee

after

backing

Democrat

Edward

J. Gay

rather

than

Republican

J.S.

Davidson

for

Congress

and

encouraged

other

Louisiana

blacks

to

follow

suit.

He

accused

the

national

Republican

Party of

having

conferred

suffrage

and

civil

rights

on

blacks

only to

maintain

the

party’s

political

majority,

of

deliberately

defeating

passage

of the

“Blair

Educational

Bill,”

of the

passage

of the

“McKinley

Tariff

Bill” to

punish

Southern

blacks

supported

by sugar

cane

cultivation,

and of

refusing

to seat

contested

black

candidates

from

Louisiana,

among

other

things.

Detroit

historian

Fred

Hart

Williams

described

the

bearded

Roxborough

as an

“independent,

astute

man who

left his

mark,

his

legal

ability

is

stamped

indelibly

upon the

legal

profession

in two

states.”

“They

came to

Detroit

for the

children’s

sake,

cause my

grandfather

was so

proud,”

Charles

Jr. told

researcher

Kathleen

A. Hauke

in 1983.

Hauke

donated

her

research

on the

family

to the

Detroit

Public

Library’s

Burton

Historical

Collection.

“He

spoke

Polish.

My

grandmother

was a

lady

from the

word go.

Real

elegant,

strait-laced.

She

looked

white,

but she

was

Creole

French

and

black.”

Charles

II was

born in

Cleveland,

Ohio in

1856. An

1860

U.S.

Census

record

describes

him as a

free

mulatto.

Not a

slave.

He

became a

lawyer

and

married

Virginia

Simms,

who was

born in

1863, on

December

23,

1886. In

Detroit,

the

family

lived

north

the

legendary

Black

Bottom

community

in an

ethnic

melting

pot of

Polish

Catholic,

European

Jews and

blacks

and

whites

from the

South.

Home was

a

matchbox-sized

dwelling

located

at 863

Chene

Street

near

Warren

Avenue.

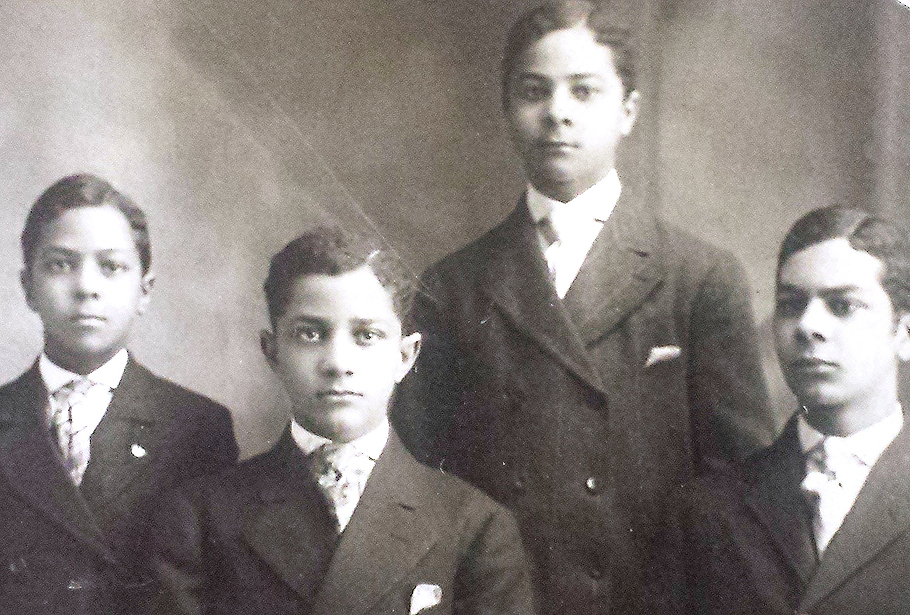

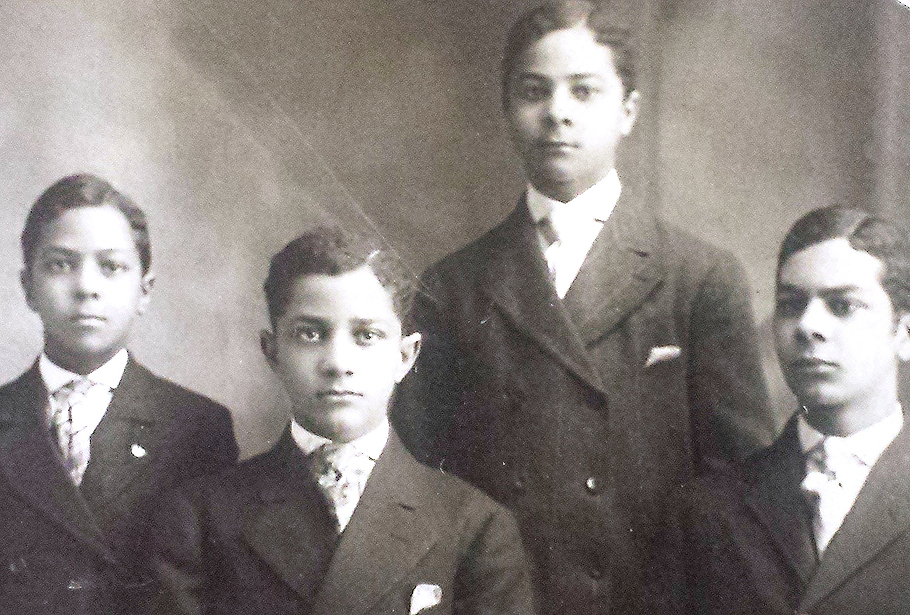

They had

four

boys:

Charles

Anthony,

born on

November

25,

1887;

Thomas

Simms,

born

April 5,

1889;

John

Walter,

born on

February

21,

1892;

and

Claude,

born in

1893.

Thomas,

a World

War I

veteran,

died

October

12,

1920, in

an

automobile

accident

in

Minnesota;

Claude

died on

September

22, 1955

of blood

disease,

specifically,

uremic

poisoning;

Charles

Anthony

died on

October

8, 1963;

John

died on

December

13,

1975.

Charles

II

became a

leading

lawyer

in

Detroit.

Fluent

in

French,

Spanish,

and

Polish,

Charles

served

clients

both

black

and

white in

the

lower

east

side

community

where

European

immigrants

were the

area’s

largest

set of

residents.

In fact,

Detroit’s

black

population

numbered

at only

4,111 in

1900

only

1.4% of

the

city’s

overall

population.

It

skyrocketed

to

120,000

by 1930.

Charles

II died

on

August

18, 1908

and wife

Virginia

died on

December

26,

1935. Of

the four

Roxborough

brothers,

only

Charles

had

children.

ROXIE

AND

CHARLEY

John

Walter

Roxborough

was a

cigar-smoking

millionaire

who

during

the

1940s

co-managed

world

heavyweight

champion

Joe

Louis

whom he

met in

1931

when the

“Brown

Bomber”

was a

teenager

learning

the

“sweet

science”

at the

Brewster

Recreation

Center.

Roxborough

was also

a

leading

gambling

racket

boss who

helped

to

operate

a policy

and

numbers

business,

a form

of

illegal

lottery,

that

landed

he and

business

associate

Everett

Watson

in

Jackson

State

Prison

between

December

29,

1944,

and

October

4, 1946.

The

front-page

scandal

centered

on a $10

million

annual

business

and led

to the

indictment,

prosecution,

and

prison

sentences

of

street

hustlers,

police

officers,

and

brass as

well as

former

Mayor

Richard

Reading.

On April

24,

1940, a

one-man

grand

jury

headed

by Judge

Homer

Ferguson

reigned

in 135

defendants,

including

78

Detroit

policeman,

and

handed

down

indictments

on

Roxborough,

his

brother

Claude,

the

former

mayor,

former

Wayne

County

sheriff

Thomas

Wilcox,

and

former

Detroit

police

superintendent

Fred

Frahm,

as well

as a

large

number

of

police

officials

and

those

accused

of

gambling.

Reading

stood

grimed

faced,

his eyes

locked

facing

directly

in front

of him,

his

hands in

his

pockets.

Defiant,

the

normally

jovial

Reading

declared:

“It’s a

lot of

nonsense.

It is

ridiculous.

I don’t

even

know

what

policy

is. I

don’t

know

what it

is all

about.”

At his

arraignment,

a stoic

and

unfazed,

Roxborough

chewing

on a big

cigar

was

quick to

declare

that

whatever

charges

were

leveled

at him,

his

friend

and

client

Joe

Louis

wasn’t

involved.

As for

Roxie,

however,

he

stated

that he

didn’t

know

“whether

he had

stubbed

his

toe.”

Roxie

was

accused

of

leading

the

so-called

Big Four

Mutual

syndicate;

Watson

was

accused

of

running

the

Yellow

Dog

policy

house.

Judge

Ferguson

declared

in June

1940:

“The

Court is

of the

opinion

that the

evidence

clearly

show

that

after

(Reading)

took

office

there

was an

agreement

between

the

parties

to this

conspiracy

and the

Mayor of

Detroit.

It is

not

disputed

on the

record

that the

Mayor

accepted

a

consideration

from the

policy

operators

through

one of

the

police

inspectors

(Inspector

Raymond

Boettcher

of the

Bethune

Station)

and

Ulysses

Boykin

(known

as the

‘Black

Mayor.’”

On

December

15,

1941, a

jury of

eight

women

and four

men

threw

the book

at

Reading,

Roxborough,

and 20

others

guilty

of

conspiracy

with

operation

of a $10

million

a year

numbers

and

policy

gambling

racket

during

the

years

1938 and

1939,

which is

about

$167

million

in 2015

dollars.

“This is

the

greatest

injustice

since

the

crucifixion

of

Christ,”

Reading

declared

at the

time.

On

January

7, 1942,

Reading

was

sentenced

to four

to five

years in

prison.

Roxborough

and

Everett

I.

Watson,

an

insurance

executive

and

manager

for

heavyweight

boxer

Roscoe

Toles,

as well

as

Walter

Norwood,

owner of

the

popular

Norwood

Hotel,

too,

were

convicted

on

related

gambling

charges

in 1942.

Roxborough

fought

the case

with

vigor

appealing

to the

state

Supreme

Court,

and

ultimately

petitioned

the

United

States

Supreme

Court

but the

nation’s

high

court

refused

to

review

the case

on

October

16,

1944.

Lloyd

Loomis,

an

African-American

former

an

assistant

state

attorney

who

family

roots

ran deep

in

Detroit,

represented

Roxie.

“I was

just a

loaner,”

Roxborough

argued

two

decades

later in

1966.

“Just

lent the

outfit

money to

get

started.”

Roxborough

and

co-defendant

Watson,

an

African-American

business

partner,

filed an

appeal

arguing

against

a

statement

that

O’Hara

made to

a

newspaper

reporter.

O’Hara,

a white

man, was

quoted

as

saying

that he

didn’t

want any

blacks

on the

jury

because

they all

played

the

numbers.

For more

than 20

years

Roxborough

and

Watson,

lived

the high

life as

two of

Paradise

Valley’s

most

powerful

men and

all that

came

with it.

Glorious

summers

at

Idlewild,

a

black-owned

resort

situated

on the

western

side of

the

state

near

Lake

Michigan.

Memorable

evenings

at the

Norwood

and

Gotham

hotels

complete

with fat

cigars,

fine

liquor,

great

music,

and

leisurely

gambling.

On

December

29,

1944,

however,

during

the

midst of

the

festive

holiday

season,

both men

were

introduced

to a

cold,

matchbox-sized,

ten-foot-long

by

six-foot

wide

Jackson

Prison

cell.

Their

iron bar

neighbors

were an

assortment

of

common

punks:

pedophiles,

dope

pushers,

serial

burglars,

con men,

and

murderers.

Sunnie

Wilson,

the

affable

entertainment

businessperson

who

owned

the

all-the-rage

Forest

Club

located

at

Forest

and

Hastings

streets

during

the

1940s

and the

Mark

Twain

Hotel on

Garfield

near

Woodward

Avenue

said

about

Roxie in

his

memoir

Toast of

the

Town:

The Life

and

Times of

Sunnie

Wilson:

“Despite

Mr.

Roxborough’s

intransigence,

I

believe

he and

Mr.

Watson

were

singled

out by

the

investigation

in order

to set

an

example.

The

city’s

attempt

to break

up the

numbers

hurt the

economic

condition

of the

black

community.

Black

Detroiters

saw the

trial as

a direct

attack

on their

community…The

only

difference

between

the

black

folks’

policy

and

state-run

lottery

is that

we had

three

digits

and

current

game has

six.”

Roxie

was on

February

21, 1892

in

Louisiana.

He

attended

Detroit’s

Eastern

High and

studied

law for

one year

at

Detroit

College

of Law

beginning

in the

fall of

1916. By

the

1920s,

he

dabbled

in the

real

estate

business.

He owned

and

published

The Owl

newspaper

during

the late

1920s

and

later

doubled

as an

insurance

executive.

By 1934,

he lived

in an

apartment

located

at 425

East

Kirby

near at

Brush

Street

on the

city’s

near

east

side.

The

block

was also

home to

Great

Lakes

Mutual

Insurance

Company,

a

black-owned

firm

that he

helped

to

found.

After he

was

granted

a

divorce

from his

first

wife,

Dora, in

1936,

Roxie

signed a

$30,000

lump

settlement

to her.

Adjusting

for

inflation,

the sum

translates

to

$510,000

today.

The set

of

proceedings,

which

included

two

circuit

court

case

dismissals

and a

failed

appeal

to the

state

Supreme

Court,

began in

1931. At

one

point,

Dora

sued

Roxie

for

separate

maintenance.

He

countered,

accusing

her of

cruelty

and

messing

around

with

other

men.

Dora

took to

him with

a

baseball

bat when

he

refused

to give

her

money,

Roxie

claimed.

On

another

occasion

Dora

shot at

him

while he

lay in

bed,

Roxie

argued.

Here are

a set of

accusations,

according

to a

1934

Michigan

Supreme

Court

case

file

called

Roxborough

v

Roxborough:

July 1,

1926,

plaintiff

and

defendant

were

married.

They had

long

been

acquainted.

October

7, 1931,

he filed

a bill

for

divorce

against

her upon

the

ground

of

extreme

cruelty,

claiming

she

nagged

and

fussed

at him;

was

addicted

to

gambling;

demanded

money of

him to

pay her

gambling

losses;

and

threatened

to leave

him if

he did

not take

care of

her

folks.

He

claims

she

absented

herself

from

home;

engaged

in

playing

poker,

or other

games of

chance;

her

telephone

bills

were

excessive,

sometimes

reaching

$100 a

month;

she

spent

money

without

regard

to

plaintiff's

welfare;

had many

charge

accounts

with

different

mercantile

establishments;

interfered

with him

during

his

working

hours;

threatened

him;

caused

him

shame,

and

interfered

with his

work;

shot at

him; and

on some

occasions

fought

him. He

asked an

injunction

restraining

her from

preventing

his

coming

home;

interfering

with him

in his

home;

withholding

his

clothes;

interfering

with his

business;

or

inflicting

personal

violence

upon

him.

Defendant

denied

all the

material

allegations

of

plaintiff's

bill of

complaint.

"She

denies

that at

one time

she shot

at him,

but

alleges

that she

did so

only

after

she was

being

given an

unmerciful

beating

from the

plaintiff

and

alleges

that it

was

necessary

to arm

herself

with a

revolver

in order

to

protect

herself

and to

save her

life."

She

affirmatively

alleges:

"That

the

plaintiff

is

associating

with

other

women

and

keeping

and

maintaining

other

women in

luxuries,

and that

because

this

defendant

has

remonstrated

with him

he has

cut off

entirely

her

means of

support."

From a

decree

dismissing

his bill

of

complaint,

plaintiff

appeals.

Although

ordinarily

there

are

three

parties

to a

divorce

proceeding,

the

State is

not here

particularly

interested,

there

being no

children

and the

parties

being

apparently

well

able to

take

care of

themselves.

They

lived

luxuriously.

Defendant

had

diamonds

worth

approximately

$10,000;

a grand

piano

which

cost

nearly

$4,200.

Plaintiff

presented

defendant

with a

Packard

automobile

as a

present,

while he

drove a

12-cylinder

Lincoln

car.

Defendant

admits

her

monthly

bills

for

household

and

living

expenses

ran

about

$1,000,

defendant

claiming

all this

was at

the

request

and with

the

consent

of the

plaintiff

who wore

$7.50

socks,

and at

one time

sported

250

neckties

that

cost

$6.50

apiece.

She

claims,

and the

proof

indicates,

plaintiff

desired

to

maintain

the

finest

home of

any

colored

man in

Detroit.

Their

nuptial

war

routinely

made

headlines

in the

local

black-owned

newspapers,

Michigan

Chronicle

and

Detroit

Tribune,

as well

national

publications

like

Ebony

and Jet.

After

marrying

his

second

wife,

Wilhemina

Morris

of

Indianapolis

also

known as

“Cutie,”

he built

a

spacious

home in

1938 on

the

North

End.

Located

at 235

Holbrook

Avenue,

the

3,500-square

foot,

six-bedroom

and

three-bathroom

mini

castle

included

a

three-car

garage.

Known to

some as

“Black

Santa

Claus”

because

of his

philanthropy

to

community

organizations

like the

local

NAACP

and

dozens

of kids

who

boxed at

the

Brewster

Recreation

Center,

Roxie

later

served

as

president

of the

Superior

Life

Insurance

Society.

Roxie

and

Cutie

divorced

in 1956.

An

uncontested

proceeding,

he

shrugged

and

shelled

out even

more

dough: A

cash

settlement

of

$125,000

and

$82,000

in

property.

Cutie

died in

1971.

When

Roxie

died in

1975,

his home

had been

on the

19th

floor of

a

federally

funded

senior

hi-rise

in

Lafayette

Park,

the

community

once

called

Black

Bottom.

Pallbearers

and

honorary

pallbearers

at his

homegoing

service

included

Major

League

Baseball

great

Willie

Mays,

boxing

champions

Joe

Louis

and

Sugar

Ray

Robinson

as well

as famed

barbershop

quartet

The

Mills

Brothers

and

legendary

composer

Eubie

Blake.

“Without

John

Roxborough’s

money,

Joe

(Louis)

would

have

never

have

become

the

world-class

fighter

we know

today,”

Sunnie

Wilson

declared.

Charles

known to

some as

“Charley”

served

in the

Michigan

Senate

for a

single

term

after

being

elected

in 1930.

The

6-foot-tall

and

fair-skinned

Republican

was a

star

basketball

player

at

Eastern

High

School

in 1905,

and a

learned

scholar

at the

University

of

Detroit

Law

School

graduating

on June

18,

1914.

Charley

holds

the

distinction

of being

the only

black

man to

participate

in a

state

convention

to

repeal

the 21st

Amendment

to the

U.S.

Constitution,

the 1933

action

that

ended

the

Prohibition

era.

Charley,

a

distant

and

detached

father,

was

arrested

in

Lansing

in 1931

during

the

legislative

term for

being

under

the

influence

of

alcohol.

“Pa

wasn’t

warm,”

Charles

Jr. also

known as

“Sonny,”

told

Kathleen

A. Hauke

in 1983.

“I

respected

him

cause he

was a

big

man—he

dressed

good,

looked

good. He

could

have

been a

Congressman

if he

had

switched

parties.

I know

he was a

periodic

drinker.

He could

have

been an

alcoholic.”

“Ma and

I were

the

closest

and we’d

go down

to the

dive and

get him

out. I

was in

my early

teens—he’d

be

broke.

We’d get

a call

from

joint on

Hastings

Street.

Ma would

drive.

We’d go

to the

back

door and

carry

him

out.”

The

North

End

resident,

who

lived at

551

King,

531

Chandler

and

later

608

Woodland,

wielded

two

unsuccessful

campaigns

for a

U.S.

House of

Representatives

seat

during

the

1930s,

served

on City

of

Detroit

Planning

Commission

and was

elected

president

of the

body in

1938,

and

co-founded

the

Gamma

Lambda

Chapter

of Alpha

Phi

Alpha

fraternity.

As a

young

man, he

worked

as a

personal

messenger

for Gov.

Chase S.

Osborn.

Two

decades

later,

he was

tapped

to serve

as an

assistant

state

attorney

by Gov.

Frank

Fitzgerald

but

turned

it down.

He did,

however,

accept

an

appointment

to the

state’s

unemployment

compensation

commission.

He

wasn’t

afraid

to

challenge

his

political

party if

he

thought

that it

was

wrong.

In fact,

in 1948

he

blasted

GOP

leaders

for

ignoring

blacks.

In 1948,

Charles

threatened

to bolt

from the

Michigan

Republican

Party

and

Governor

Kim

Sigler

because

of their

shoddy

track

record

on civil

rights

and

equal

opportunity

issues:

In a

letter

to

Emmett

J. Scott

of the

Republican

National

Committee,

Roxborough

declared

that 90

percent

of the

Negroes

of

Michigan

will

vote

Democratic

because

‘nothing

has been

done in

Michigan

by our

Republican

Governor

or the

Republicans

locally,

to keep

the

Negro

vote in

the

Republican

column.

“In all

my years

of

politics

I have

never

seen

such a

situation

as

exists

today—white

Republicans

attempting

to run

Negro

Republicans

out of

the

Party

and

treating

other

like

they do

in the

State of

Mississippi.

Charley

went

into

semi-retirement

with his

wife,

Hazel,

on their

farm

near

Milford.

He died

on

October

8, 1963,

at age

75.

Charley

had four

children,

and

married

three

times to

Cassandra

Pease of

Hamilton,

Ontario

on June

30,

1913;

Lottie

Grady,

an

effervescent

singer

and

dancer

from

Chicago,

in 1919;

and

Hazel A.

Lyman,

an

official

at

Detroit

Recorder’s

Court,

in 1944.

Charley

and

Lottie

divorced

in 1939.

During

the

proceeding,

Charley

testified

that he

found

letters

in his

home

indicating

that

Lottie

was in

love

with

another

man. His

kids:

Elsie,

Virginia,

Charles

Jr., and

John

Walter

were

born

between

1914 and

1922.

The

girls’

mother

was

Cassandra;

the

boys’

was

Lottie.

“In the

(Great)

Depression

we had

money,”

Sonny

recalled

many

years

later in

1983.

“we had

money;

later,

when

other

blacks

had

money,

we

didn’t”

Soaring,

slender

and

striking,

Elsie

was a

1937

University

of

Michigan

graduate

and

playwright

who was

romantically

linked

with

Harlem

Renaissance-era

poet

Langston

Hughes

and

world

heavy

weight

boxing

champion

Joe

Louis.

With

large

and

forward

sitting

eyes

like

actress

Bette

Davis

and

bearing

a

resemblance

to

another

Hollywood

star

Tallulah

Bankhead,

Elsie

edited a

newspaper

called

The

Guardian,

which

was

owned

and

operated

by

Charles

Roxborough,

her

father.

In 1935,

the

Chicago

Defender

published

a

front-page

story

about

she and

Louis.

In the

story,

Elsie

flatly

denied

that she

and

boxer

were

engaged

to be

wed:

“Joe and

I are

friends

and my

career

as a

writer

is much

more

important

to me

than the

thought

of

marriage...I

do think

Joe is a

fine

fellow

and well

deserving

of any

girl.”

After

moving

to New

York

City

during

the

1930s in

search

of

career

fortune,

she dyed

her hair

Lucille

Ball-like

auburn

and

lived as

a white

woman

named

Mona

Monet.

Her

plays

were

presented

in

Detroit

such as

Langston

Hughes’

Drums of

Haiti

and an

adaptation

of

Walter

White’s

novel

Flight.

She had

a

screenplay

embraced

by

Hollywood

and she

wrote

feature

magazine

articles

while in

New York

City.

Elsie

died

October

2, 1949,

of an

overdose

in her

Manhattan

apartment

located

at 865

First

Avenue

one

block

from the

East

River.

She was

identified

as white

on her

death

certificate.

Family

and

friends

debated

whether

it was

accidental

or

suicide.

Elsie

was

described

as

ambitious

and

high-strung

yet at

times

single-minded,

lonely

and

depressed

over the

challenge

of

becoming

a

successful

playwright

and

overcoming

racism

and

sexism.

Her

death

made

front-page

news in

the

Michigan

Chronicle.

Bill

Lane

wrote in

its

October

8 issue:

“Energetic

people

find it

hard to

sleep at

times.

Sleeping

pills

come in

handy.

But

sometimes

one can

take too

many.

Elsie

took too

many.

Suicide?

No.

Elsie

was the

type of

girl who

would

leave a

note for

everyone

in the

Roxborough

family

if she

contemplated

suicide.

She left

no

note.”

“Elsie

Roxborough

was far

ahead of

her

time,”

Ulysses

W.

Boykin

told

researcher

Kathleen

A. Hauke

in 1983.

“She

would

have

found a

place

for her

talent

and

recognition

now. In

her

time, it

was

quite a

struggle

for

blacks.

You

could

‘pass’

and get

lost, or

if you

stood

out, it

was an

unsuccessful

road.”

Julia

Cole

Bradby,

a friend

of

Elsie’s

who

participated

in the

playwright’s

theater

troupe,

Roxane

Players,

did not

believe

that she

committed

suicide.

Bradby

cited

that a

pair of

stockings

in her

apartment

had been

washed

and hung

to dry.

Bradby

argued

that

Elsie

accidently

overdosed

after

drinking

whiskey

and

digesting

sleeping

pills.

However,

“Sonny”

Roxborough,

her

half-brother,

suggested

in 1983

with

researcher

Kathleen

A. Hauke

that

Elsie

took her

own

life:

“Elsie

was so

educated,

and

there

was

nothing

for

blacks.

She got

hung up

in the

big

city.

She was

very

emotional

and

high-strung.

She had

so much

ability,

like a

fine-bred

racehorse,

the way

she

carried

herself.

Her

walk;

she

walked

like a

thoroughbred.

She

couldn’t

handle

the

stress.

She

could

pass for

Spanish,

but she

didn’t

like

passing.

She

hated

it. She

committed

suicide,

you

know. I

don’t

believe

that she

did it

over,

Langston

Hughes.

She

loved no

one

man.”

Charley’s

son,

John II,

was a

star

track

athlete

at the

University

of

Michigan.

He also

became a

lawyer

and

worked

as an

attorney

for the

Detroit

Branch

NAACP

from

1950 to

1954

fighting

against

racism

in

housing

and

other

civil

rights

issues

as chair

of the

organization’s

legal

redress

committee.

He later

worked

as a

U.S.

state

department

official

and

adviser

to

Secretary

of State

John

Foster

Dulles

during

the

Dwight

D.

Eisenhower

Administration.

“In the

bustling

Paradise

Valley

sector

with its

jam-packed

Negro

population,

the word

is when

you get

in

trouble

and need

a

lawyer,

‘take it

to young

Roxborough,”

a 1960

feature

on the

Roxborough

family

in Sepia

magazine

stated.

“He

knows

what to

do in

court.”

John II

was born

January

7, 1922;

he died

June 13,

2011. He

married

June

Baldwin;

they had

two

children:

Claude,

a

lawyer,

born in

1948;

and John

W. III,

a

dentist,

born in

1949.

June

died on

November

21,

2014.

John II

later

married

Mildred

Bond,

executive

assistant

to Roy

Wilkins,

executive

director

of the

NAACP,

in 1964.

Virginia

and

Charles

Jr. were

well

known

throughout

Detroit

and

Idlewild,

the

popular

black

vacation

resort

on

Michigan’s

northwest

side

near

Lake

Michigan.

Virginia

also

attended

the

University

of

Michigan

after

four

years at

Detroit’s

Northern

High

School.

In 1938,

she

married

Benjamin

Brownley,

a

Cleveland

native

and

podiatrist.

“Virgie,”

a

secretary

at Cass

Technical

High

School,

died in

1982

after a

valiant

fight

with

cancer.

Benjamin

died in

1999.

They had

one

child,

Blyss

born in

1953.

Charles

Jr.

(Sonny)

moved to

Idlewild

in the

1940s

and

retired

as a

substance

abuse

counselor

at

Regional

Health

Care in

Baldwin.

He

married

Loraine

in 1938.

They had

two

children:

Carol

and

Charles.

“Sonny”

died in

2003.

PRESERVING

THE

LEGACY

“The

whole

family

could

have

been

considered

snobbish,”

said

Kermit

Bailer,

a

well-known

attorney

who grew

up in

Detroit

during

the

1920s,

‘30s,

and

‘40s. He

described

the

Roxboroughs

as

“aloof,

private

and

withdrawn.”

Bailer,

a former

John F.

Kennedy

Administration

housing

official

and Ford

Motor

Company

attorney

who died

in 1996,

had

Roxie as

a client

during

the

1950s.

He

described

him as a

“fine

gentleman”

who was

“highly

regarded.”

About

the

Roxboroughs

and

their

relationship

to other

blacks,

Bailer

summed

it up

this way

during

an

interview

with

Kathleen

A. Hauke

in 1983:

“It was

because

of color

consciousness

within

the

black

race.

Every

black

was

always

struggling.

As

compared

to the

universe,

they

were

snobbish.

There

was a

lot of

antipathy

between

the

light-skinned

blacks

and the

dark-skinned

blacks.”

Today,

the

Roxborough

family

name

lives on

through

Charles

A.

Roxborough’s

great,

great

grandchildren

Claude

Roxborough

III, a

lawyer,

John

Roxborough,

IV, a

medical

doctor,

Erin

Roxborough

as well

as other

family

members.

Ken

Coleman

is a

Detroit-based

author

and

historian.

He wrote

about

the

Roxborough

family

in his

book

“Million

Dollars

Worth of

Nerve.”

He can

be

reached

at

www.onthisdaydetroit.com

|